A recent Financial Times article on foreign direct investment (FDI) in Ukraine has focused on two major arguments. First, new FDI in Ukraine fell abruptly after the conflict with Russia started. Second, despite some notable improvements of the business environment in Ukraine, political and security issues stop FDI from recovering.

It is important to realize though that most of pre-war FDI actually originated in Ukraine (and Russia) and came through special purpose entities. And while the uncertainty around the military conflict with Russia limits investment, the Ukrainian government will have to address the long-standing obstacles to FDI if it hopes to increase the odds of attracting genuinely foreign capital into the country.

Following the Euromaidan, the annexation of the Crimea and the onset of warfare in Donbass, FDI inflows in Ukraine declined drastically, from $4.5 billion in 2013 to $410 million in 2014. No doubt that the military conflict with Russia, as well as the political and economic crises it caused, are to blame.

FDI started to fall even before the events of 2014. Already in 2013, FDI fell by 46.4% (from $8.4 billion in 2012), due to a slump in the demand for Ukrainian exports, the deteriorating political situation and economic uncertainty. A similar downturn occurred in 2009, when FDI fell by 56%, following the abrupt decrease in worldwide investment flows in the wake of the global financial crisis.

However, the tenfold drop in FDI in 2014 was unprecedented both for Ukraine and for neighboring countries. Despite a certain increase in 2015 ($2.96 billion) and in 6 months of 2016 ($2.13 billion), FDI has failed to return to its 2013 or 2012 levels. Importantly, this increase is to a large degree explained by the recapitalization of banks with foreign capital, while the amount of greenfield investment remains low.

However, was the pre-war FDI in Ukraine genuinely foreign? And how strong has the influence of the military conflict in Donbass on FDI been?

The origin of FDI in Ukraine

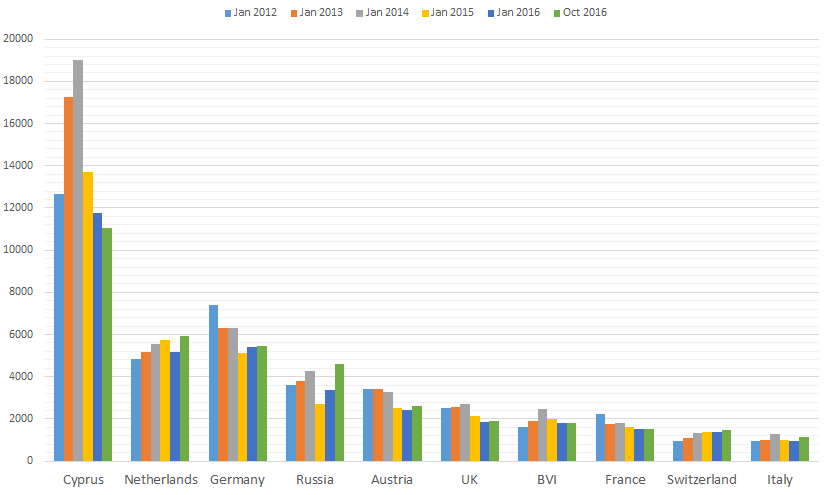

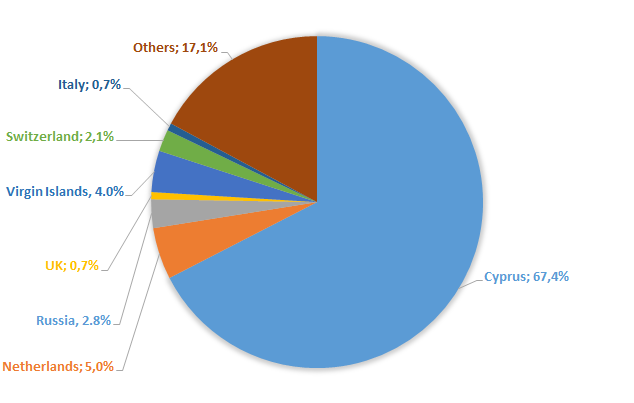

Cyprus has traditionally been the largest source of FDI in Ukraine (Figure 1). As of January 2014, the share of Cyprus-registered investors in the FDI stock was 32.7%, while currently it equals 24.4%. Three tax havens, Cyprus, British Virgin Islands, and Belize, together account for 29.6% of FDI stock (38.8% at the beginning of 2014).

Investments from Cyprus and other tax havens are usually of Ukrainian or Russian origin. Investors use special purpose entities (SPEs) in those countries in order to pay less tax and to acquire a special legal status etc. For instance, according to a study cited by the OECD Investment Policy Review, real Russian investment in Ukraine was at least thrice as large as the official data suggested at the end of 2014 (about $9.9 billion compared to $2.7 billion).

At first glance, such developed countries as Germany and the Netherlands also seem to invest quite a lot in Ukraine. Yet German FDI mostly comes from Indian ArcelorMittal, the largest foreign investor in Ukraine, which uses its Germany subsidiary to control a steel plant in Ukraine.

Similarly to Cyprus, the Netherlands is a popular conduit for capital from all over the world and ranks only formally among the largest global sources of FDI. For instance, part of $1.8 billion of its FDI stock in the telecommunications sector in Ukraine comes from Dutch-registered VimpelCom, which owns Kyivstar, the largest Ukrainian cell-phone operator. Yet the largest owner of VimpelCom (through intermediaries) is Russian Alfa-Group. Genuine FDI from the Netherlands is actually not that large and is represented, e.g., by Unilever[1] .

The origin of FDI in Ukraine becomes even more evident when we look at the sources of the growth of FDI stock in the years immediately before the crisis (Figure 2).

In 2012, Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands accounted for 71.4% of the net increase in the FDI stock in Ukraine. Their share fell to 52.9% in 2013. Following the onset of the armed conflict, investment from Cyprus declined the most as offshores were mainly used to invest in the East of Ukraine, hit by the conflict and the economic crisis.

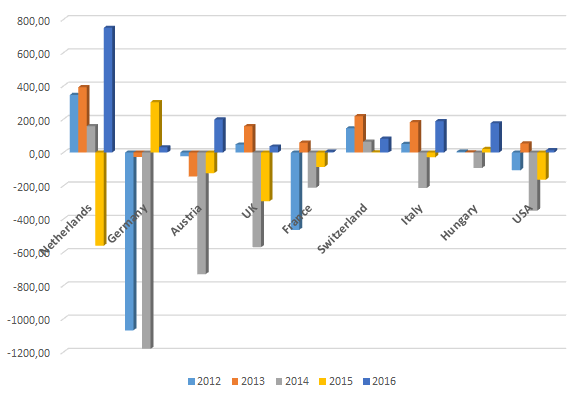

Compared to FDI from Cyprus, investment from other countries may appear rather insignificant. Figure 3 shows the dynamics of FDI from other major sources of investment (excluding two obvious tax havens, Cyprus and British Virgin Islands, and Russia).

The growth of investment from the Netherlands and Switzerland mostly reflects the reinvestment of Ukrainian and Russian capital. For instance, in February 2016, a Dutch-registered subsidiary of Rinat Akmetov’s DTEK increased its share in the largest private gas producer in Ukraine, “Naftogazvydobuvannia”, to 55%. At least one of the co-owners of Risoil, a Swiss-registered company that invested $70 million in the construction of a grain elevator in Illichivsk seaport in 2014-2016, is a businessman from Ukraine.

The changes in FDI from other countries have been largely caused by investment in the banking sector. For instance, it is the recapitalization of foreign-owned banks that led to the increase of FDI stock from Austria («Raiffeisen Bank Aval» і Unicredit[2] ) and Hungary (OTP).

Therefore, the drop in the FDI after the beginning of the military conflict with Russia is actually the result of a sharp fall in the reinvestment of Ukrainian and Russian capital through offshore conduits. It was primarily caused by the economic crisis and uncertainty in the wake of the military conflict and political struggle.

The discussion should thus focus not on how to return to the pre-war FDI levels, but rather on how to attract genuine FDI in Ukraine. Just how important is the impact of the military conflict with Russia going to be in this regard?

Military conflict as a threat to FDI

War can divert foreign direct investment by causing the death of employees and physical loss of investment, as well as difficulties with supplying inputs or sharp fall of internal demand. Conflicts can also lead to unfavorable changes in government policies.

Indeed, according to a large study by MIGA, the number of new investment projects in conflict-affected countries drops by 34% after a significant conflict, while the value of invested capital declines by 90% on average. Military conflicts thus seem to affect larger investment projects more than the smaller ones.

Investors are forward-looking and often able to predict the onset of a conflict. As a result, FDI sometimes falls before the conflict actually starts.

At the same time, the impact of a military conflict depends on its nature, duration and scale, which are often more important than the actual warfare or its probable onset. For instance, a bloody civil war has caused FDI inflows in Syria to come to a complete halt. In Ukraine, a protracted conflict in the East and the threat to the country’s integrity caused FDI inflows to shrink more than tenfold. In Georgia, the five-day war with Russia in 2008 contributed to a threefold decline of FDI.

Military conflicts affect different sectors of economy in different ways. Investment in industries with high fixed capital intensity is highly deterred by conflict. Investment that is aimed at the internal market, especially in services (except telecommunications and financial sector) and durable consumer products, also seem to suffer more.

Irrespectively of the sector, investment is less affected if the potential return on investment is deemed high enough to compensate the risk. Indeed, the return on investment in conflict-affected countries is 50% higher than the average return in low-income countries. Higher return partially explains why investment in the primary sector is usually more stable.

How long can the negative influence of military conflicts on FDI last? According to some estimates, FDI starts to rise about three years after the end of large-scale (>1000 deaths) military conflicts. Another study suggests that the history of frequent military conflicts creates an enduring risk of investing in the country. However, not everyone agrees.

There are no separate studies that look at FDI trends in the countries with “frozen” or “simmering” conflicts. Yet the political risk of investing into these countries is usually viewed as high or very high, which has a significant negative impact on investment. The MIGA survey shows that political risk[3],

together with the macroeconomic stability, is the most important factor considered by investors at the three-year horizon.

In countries with “simmering conflicts”, investors remain very sensitive to the level of violence. For instance, a link exists between the increase in the intensity of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the outflow of capital from Israel. In 2014, after the unexpected seven-week military operation in the Gaza Sector, the FDI inflows in Israel fell by 50%.

The future of FDI in Ukraine

The military conflict with Russia will continue to affect FDI inflows in Ukraine. On the one hand, the warfare is limited to a small part of Ukraine’s territory. Its intensity has decreased from its heights in 2014-2015. However, given the unpredictability of Ukraine’s opponent and the continuing warfare along the contact line, the perceived political risk of investing in Ukraine remains very high.

Moreover, as this report on investment climate in Ukraine notes, “due to extensive media coverage of the conflict in international media, the whole country is to a large extent associated with the military conflict in the East” and no clear distinction is made between regions of Ukraine. In order for this difference to become evident to a larger number of potential investors, more time has to pass without major escalation, while an active information policy and the success of existing foreign investment would also help. Another concern is whether Ukraine can offer projects with a return high enough to cover the risk of investing in the country.

Yet the fighting in the East has not scared off some (genuinely) foreign investors. For instance, French Biocodex has invested in the relatively stable pharmaceutical industry. US-based Cargill and Chinese Cofco invest in agricultural logistics. France’s Nexans and Japan’s Fujikura have built production facilities in Lviv region, finally seizing on such advantages of Ukraine as its educated and cheap workforce, as well as the proximity to the EU market. The success of these investments could become a signal for other potential investors.

Indeed, investors pay attention to a plethora of factors, both of economic and political nature. According to the MIGA survey, the concerns of investors in conflict-afflicted countries are more focused on unexpected and arbitrary changes in government policies in relation to their investments than on security issues. 62% of respondents named “regulatory changes” as their top political risk concern, while only 15% and 4% responded that war and terrorism were the main threats to their investments. In developing countries, more investors have experienced losses after the government intervention than because of a military conflict — through regulatory changes, breach of contract, restrictions on transfer and convertibility of profits and incomes, or non-honoring of sovereign guarantees.

According to a survey by Ukraine-based Dragon Capital, potential investors are less preoccupied with the military conflict with Russia than with widespread corruption and lack of trust in the judiciary. Unpredictable currency and unstable financial system, as well as restrictive capital controls, are only slightly less important than the security issues. The survey might underestimate the influence of the military conflict, as the respondents are already interested in investing in Ukraine despite the hostilities in the East. Yet the survey reminds that the military conflict is only one of many factors affecting foreign investment in Ukraine.

Most of pre-war FDI in Ukraine was actually the re-invested Ukrainian and Russian capital, which means that key factors that keep genuine FDI away from Ukraine existed before the onset of the conflict. These obstacles still need to be addressed. As OECD underlines, “While the political and security situation has deteriorated in recent years, the problems are long-term and have to do with poor business environment, weak institutions, and widespread corruption.”

OECD further notes that, “The temptation is always strong to overcome these problems through specific measure to promote and facilitate targeted investment but the emphasis should rather be on improving the business environment throughout the whole spectrum of policy areas.”[4]

The improvements in the business environment, mentioned in the FT article, such as scrapping some of Soviet-era regulations and the introduction of Prozorro state procurement system, are only first steps in the right direction. If the long-term problems are not addressed, in light of the conflict with Russia and mildly pessimistic predictions about global FDI flows in 2017 and 2018, there is no reason to expect a substantial growth of genuinely foreign direct investment in Ukraine.

Notes:

[1] According to OECD, only about $558 million of FDI stock in Ukraine comes from the companies that operate in the Netherlands, while the rest comes through special purpose entities (SPEs). Interestingly, OECD data put the total Dutch investment in Ukraine at a higher number than the Ukrainian statistics office ($11.42 billion in contrast to $6.4 billion).

[2] Italian Unicredit operates its investments in European countries through its Austrian subsidiary Unicredit Bank AG. The recent sale of Ukrsotsbank to the Russian Alfa Group will therefore be reflected as a drop in FDI from Austria, not Italy.

[3] In addition to the presence of a military conflict or ethnical tensions, political risks are defined by the stability of government, as well as the predictability of its policies and the chances it will honor its promises to investors etc.

[4] The main challenges thus lie not so much in creating specific conditions for foreign investment. In the FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, Ukraine ranks higher that most non-OECD countries.

By: Rostyslav Averchuk, Guest Editor at VoxUkraine http://voxukraine.org/